I’ve been either somewhat adjacent or wholly embedded in the personal watercraft (PWC) industry for roughly 18 years (as I can measure) and I can say with some surety that this industry is changing. Of course, change isn’t anything new and it shouldn’t surprise anyone, but the direction of this latest change is what concerns me.

As far as I can see, there have been three major (and I mean full scale, tectonic-level) changes in this industry that comprehensively changed the landscape – with a fourth currently underway.

First, I’m not counting the introduction of the 1972 JS400 “JetSki” from Kawasaki as that is less of a change as much as it was the beginning. Rather, I’m looking at events that altered the trajectory from that point forward.

The original JetSkis were small, uncomplicated and required a degree of athleticism to master, which effectively made them exclusionary to casual entrants looking for a leisurely pastime. That is, until 1986 when Yamaha revealed the WaveRunner, providing a somewhat stable 2-seater platform that was less challenging and far more accessible.

Now “jet skiing” was available to everyone. This was the first of these industry-changing events.

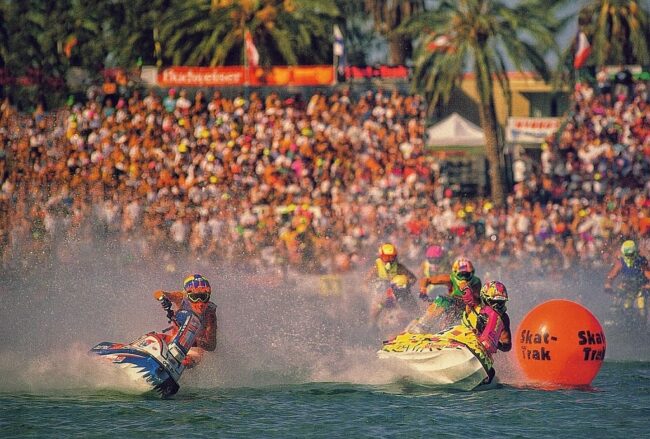

The advent of the “sitdown” sparked Bombardier’s return to personal watercraft in 1988. Suddenly, sitdown sales rivaled that of standups, and waterways were filled with all types of riders. By 1991, sitdowns were introduced into professional racing – previously exclusive territory of standups.

This period took us to 1995, which marked the industry’s all-time peak for new unit sales. As I understand, that number was as high as 155,000 units sold in a single year. The newfound popularity of PWC drew in new manufacturers like Polaris and Tigershark with each OE offering dozens of models and trim levels.

Suddenly, everyone owned a jet ski. They were cheap, easy to work on, easier to repair and parts were plentiful. Conversely, every body of water was packed with rowdy buzzing 2-strokes jumping boat wakes spouting plumes of blue smoke and leaving prismatic snail trails in the water.

While few will look at 1995 as I do, I see this as the industry’s breaking point – and the second biggest pivot point in our industry. Why? Because it was at this time that the public’s tolerance for PWC was pushed to its limit, and the years that followed were a procession of legal actions outlawing skis from lakes, shorelines and public waterways.

Without the explosion of popularity in 1995 and the legal backlash that ensued, we wouldn’t have seen the industry forced into developing 4-stroke powertrains. In 2002, Sea-Doo was going to roll out its new 4-tec 1503 3-cylinder first, but Yamaha poured on the gas and rushed out its 4-stroke FX140 on the exact same day.

It is here, with the advent of the 4-stroke engine that I submit the third biggest change in our industry occurred. Although the move to 4-strokes eventually pushed Polaris and Tigershark out, it did welcome Honda into the fray that same year. Shortly thereafter, Kawasaki joined it’s competitors finalizing the era of smog-compliant 4-strokes.

Equally, the performance aftermarket either had to convert, hold fast or fade away. Like Hemingway, once household brand names like Performance Jet Ski (PJS), Mobby’s, Pro-Tec and Beach House vanished gradually, then suddenly.

Unfortunately, 4-stroke engines were far heavier than 2-strokes and relied less on low-end torque but high RPMs to generate horsepower. Carburetors were replaced with clunky electronic ignitions and digital fuel delivery systems adding even more weight and greater sensitivities to water intrusion.

Watercraft ballooned in size as heavier internals required greater buoyancy. Wider, more stable craft also welcomed less athletic riders whose purchasing power pushed manufacturers to cater to their demands over the slim number of racier riders. Skis swelled further, more endowed with gadgets, digital features and novelties.

Is this tidal surge of technological accessories the next change mentioned at the beginning? No, although it is significantly altering our industry. Rather, the next change is far less visible to the outward observer: the trajectory of future watercraft are being directed by focus groups, emailed questionnaires and sampled dealerships instead of enthusiasts.

Look, I’m not naive. Seeking maximized sales has always been the name of the game, but previous industry stewards knew who they were targeting. Today, OE’s are staffed with corporate ladder-climbers and marketers – gone are almost all of the diehards who built each brand’s respective watercraft divisions – and they don’t know how to create new and exciting product.

Here’s some wisdom: focus groups can only react to what’s currently happening – they can’t tell you what’s coming. The most successful companies understand that reacting to ever-shifting trends (instead of setting them) has forever been a failed business model. Always chasing “the latest thing” is often costly and if response is too slow, ineffectual.

If the PWC industry was to learn anything from tech mega-giant Steve Jobs’ success, it is that the product should always drive the demand, rarely the inverse. Currently, I and many others recognize Sea-Doo as the industry’s leading innovator. It’s a dangerous position to hold as the gamble can fail spectacularly or hit the ball out of the park.

As far as I can tell, for every one failure, BRP has enjoyed three successes. This forward-thinking posture also has given Sea-Doo the upper-hand as being the brand that seems to care most about performance enthusiasts; changes made for the 325 ACE directly target the top echelon of tuners and racers – and that speaks volumes to this tight-knit community.

My hope is that Sea-Doo’s most recent moves shake Kawasaki and Yamaha awake to the value in directly addressing the core enthusiasts first before sampling the opinions of a focus group or dealership managers. If not, I don’t see this industry coming around this last corner.

Go get wet,

Kevin