“The best laid plans,” I murmured to myself as I squinted at my phone in the dark. I had been in bed for two days now, laid out with what I thought was the flu. In another day, I would discover that no, influenza was not attacking my body but a severe case of covid pneumonia. Peering through the darkness at my dimmed screen, I was conversing with Billy Duplessis and Ricky Johnson on a group chat relaying the bad news. I wouldn’t be able to attend The Watercraft Journal’s second long-distance endurance ride.

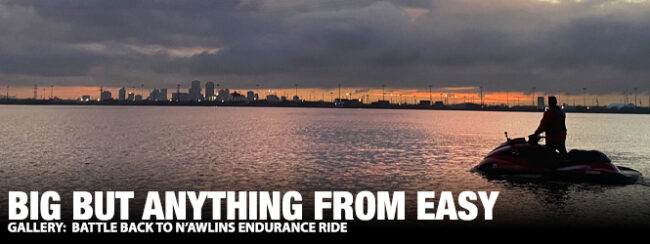

Titled “The Battle Back to N’awlins Ride,” the route Duplessis and Johnson had mapped out was well over 270-miles, leaving from downtown New Orleans, Louisiana, cutting through Lake Ponchartrain (passing two ancient military forts along the way), on to the Barrier Islands off the Mississippi Coast – consisting of Cat island, Ship Island, Horn island, and Petit Bois Island – into Alabama to our final island, Dauphin Island. To say I was disappointed to report the news to them is an understatement.

Being the super solid guys that they are, they wished me a speedy recovery and vowed to take whoever arrived out on the ride regardless of my absence. As Friday, December 17th approached and news of my illness spread, the number of attendees began to thin. With the magazine unable to attend, so went the promise of handing out giveaways and the few prizes I had as well. Johnson shared, “[It was] very disappointing that others didn’t even show from surrounding states to take us up on the endurance ride challenge.” Citing the lack of “bait” to bring them in.

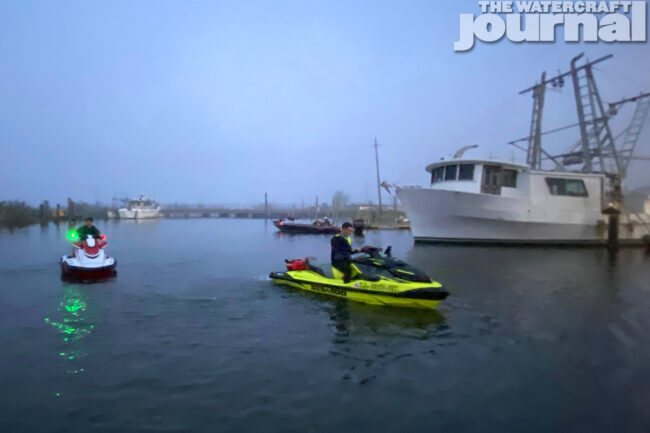

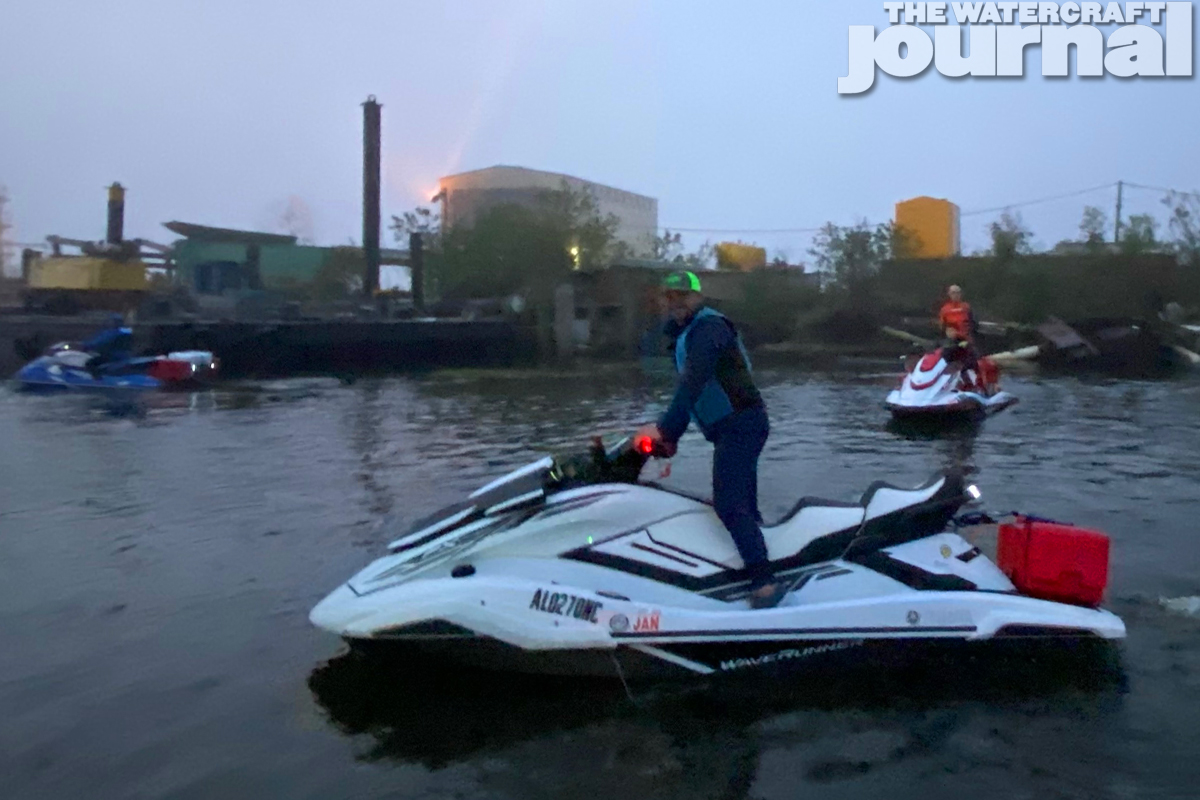

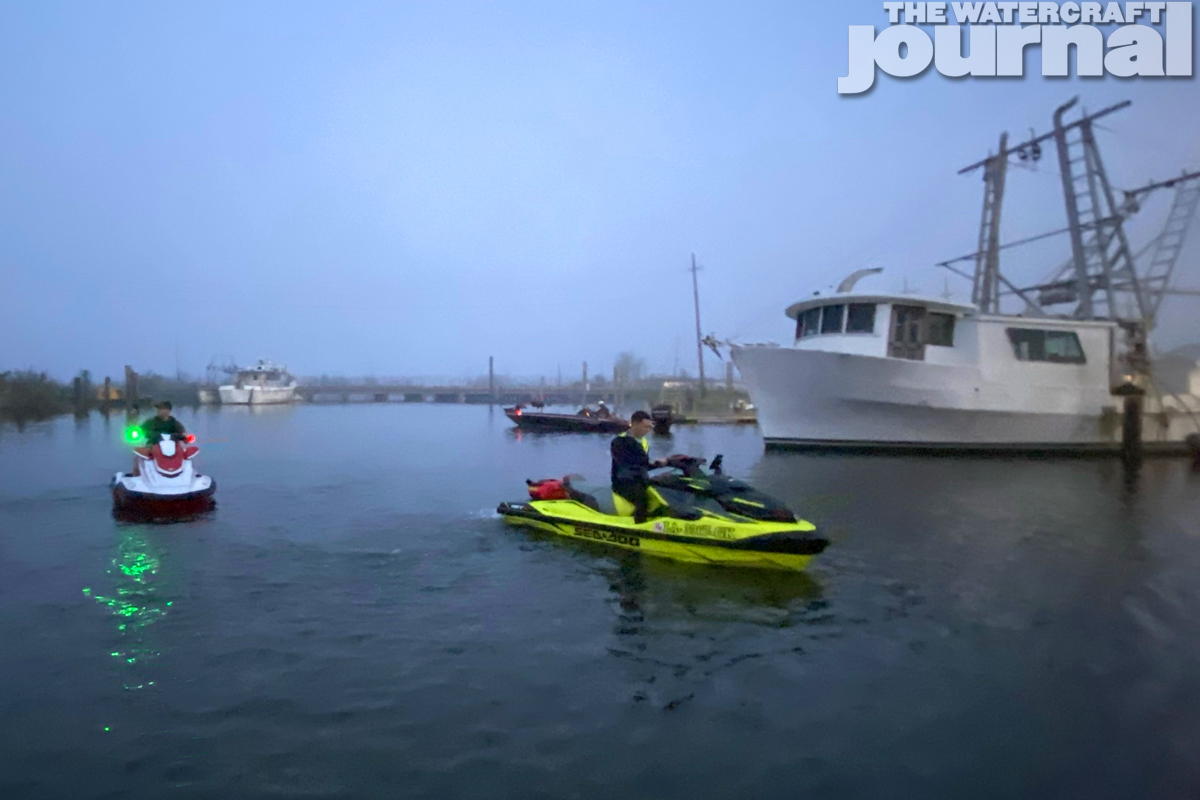

Even so, 11 hardy adventurers filled the launch ramp well before daybreak. With the promise of a full day’s ride, few knew what Mother Nature had in store. Duplessis recalled, “We faced challenges all the way up to the day of the event. Most were out of our control, including you getting sick days before. From foggy conditions until the early evening hours, cooler temps than predicted and rougher open water conditions.”

Johnson echoed Duplessis’ report, “What did affect the […] ride was shutout fog lasting well into mid-morning and me having to slow us down to 35mph relying mostly on GPS for direction with marine traffic present. The fog was so thick it was literally soaking us and you had to keep wiping it from your face.” Cutting the pace from 55-60mph to 35 crushed the original plan of 270-plus miles. With zero visibility, safety over speed was the goal.

“With two experienced leaders,” Duplessis added, “we overcame those challenges and made the hard decisions, some of which was best for the current situation and for the group.” Hitting the planned fuel stop prior to exiting out into the Gulf, the group faced seas were the other variable that distanced them from making their goal.

Johnson continued, “We experienced 15-20mph winds, tide going out, causing 2.5–to–3.5 foot seas with a wave period and direction [so] far apart that [it] wouldn’t allow us to stay on top and left us falling in the troughs.” The going was slow and brutal to say the least – then disaster struck. One of Johnson’s stainless steel marine-grade ratchet strap snapped, jettisoning his 18-gallon fuel tank.

Several lunged for the quickly-sinking tank, but it was gone within seconds. Johnson blocked off his Yamaha’s vent lines allowing for normal operation. Soon after, a second auxiliary tank slipped off of another rider’s transom, but was gratefully saved at the last moment. The turnbuckle was re-tightened and the tank reattached. The seas were simply beating the group apart.

Throughout the trip, whenever Duplessis and Johnson found a strong enough signal, they would pass along updates and images. From my sickbed the distressing reports looked dire, like the dispatches coming in from the RMS Titanic’s radio room. I honestly felt I had setup my friends to fail and there was nothing I could do. In my fevered delirium I was convinced that this was all my fault.

Despite the flogging, the group soldiered on. “We didn’t stop for lunch to regain our strength,” Johnson recounts. “The only stop we made was at Cat Island so Billy and I could talk about conditions before presenting it to the group for a vote, while everyone indulged on wet sandwiches from water bottles busting in their coolers.”

A new abbreviated route was agreed upon, and the caravan continued fulfilling a 10-hour day with 3 fuel stops comprising of 240-miles. In the end, the duo convinced me that the ride was anything but a disaster – and was, in fact, quite successful given the hurdles in their path. Duplessis boasted, “We still managed to pull out an amazing trip. I believe the ones who made the event ride would completely agree.”

Johnson joked, “We compiled over 240 miles with nearly half [of it] being in open water with nine middle-aged men. Given the weather conditions we consider it a success. If anything, that’s a testament to the endurance ride we had planned, most must have been too scared to even show [their] faces. I don’t know many that would even take on a 240-plus-mile ride on a 90-degree, bright and sunshiny day, while riding in calm flat water conditions.”

All photography provided by Billy Duplessis and Ricky Johnson