It’s difficult to properly project the future, but as one might find, looking back and tracing the trajectory that lead us to where we currently stand is quite easy. History has a way of clarifying how ripples made at one end of the pool can cascade into waves at the other end.

As we spend much of this New Year’s holiday reflecting back on the year and contemplating the future, we also want to take a look back at the personal watercraft industry as a whole; to trace back to those particular makes and models that truly changed the course of the industry, aftermarket and the sport, for that matter.

Obviously, Clayton Jacobsen’s first 1968 Sea-Doo could be included here, but again, we’re looking at impact. Those early Sea-Doos were seen as kitschy toys, not a whole new industry. Likewise, the first Yamaha WaveRunner and Sea-Doo runabouts could be seen as “missing in action,” and to a degree you’d be right. Again, we’re looking at how specific models changed the course of the industry.

Certainly, there will be models that many feel are missing and that is likely true. Yet, we selected these particular machines for their impact both at the time of their release and for the generations that followed. Hopefully, many of you will agree with our selections.

1982 Kawasaki JS550

First introduced in October 1972, Kawasaki’s WSAA and WSAB “JetSki” models were powered by modified 400cc 2-stroke twin cylinder engines. The JS400 was succeeded by the JS440 in 1977, offering more power and performance, and enjoyed popularity for well over a decade. Yet, it was 1982’s JS550 that truly placed Kawasaki’s JetSki on the map. The redesigned “mixed flow” pump spun by more powerful 531cc engine, which came with an industry-first automatic rev limiter – pretty advanced stuff for the time.

These features catapulted the JS550 into the spotlight of performance enthusiasts and the newly created sport of “jet ski racing.” Although a budding series in the late 1970’s and early 1980’s, jet ski racing opened up to the widest audience and welcomed the sport’s greatest racers with the JS550. The JS550 continued to improve into the 1990s, when it was finally discontinued.

1993 Yamaha WaveBlaster

Five years into it’s first foray into personal watercraft, the Yamaha Motor Corporation introduced the 1993 WaveBlaster. Contrary to claims that the ‘Blaster was a response to Kawasaki’s X2 single-seater “runabout” first introduced in 1986, Yamaha borrowed more from its SuperJet standup and motorcycle line in developing the “muscle craft.” Powered by a Marine Jet 700TZ, a 701cc two-cylinder, 2-stroke producing 63-horsepower and pushing the craft upwards to 44mph.

The WaveBlaster’s ability to perform acrobatic maneuvers with precision, as well as outpace other runabouts around buoys earned the Yamaha legendary status. The WaveBlaster was only produced between 1993-through-1996 (with an extended production run for Australia until 1998). This is particularly surprising given the ski’s popularity that continues even today, with a vast aftermarket and presence in the racing industry.

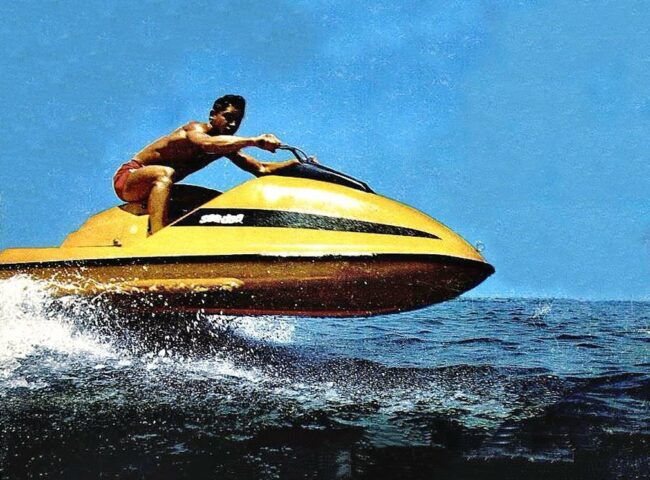

1997 Sea-Doo XP

By the time of its introduction, three previous generations of Sea-Doo had worn the XP name. Equally, a previous HX model had first debuted Sea-Doo’s articulated, suspended seat technology. Yet, it was the culmination of these features as well as the redesigned “dolphin-inspired” Coke bottle-shaped hull and deck that gave this particular Sea-Doo it’s iconic status. In fact, much of the XP’s styling carried well past its 2004 conclusion, continuing onto the 2004 RXP (and eventual RXP-X) all the way until 2011.

Many found the hull impressively responsive, fun, playful and most importantly, aggressive, leading to its strong presence on the race course. Moreover, the “Direct Action Suspension” worked to not only soak up shock but also compress during tight turns. Albeit a substantial 90-pounds heavier than its predecessor, its 110-horsepower 782cc engine was a direct carry-over.

2002 Kawasaki STX-R

Possibly the single-most important runabout ever built by Kawasaki, the STX-R was as close as a manufacturer got to selling a truly race-ready machine to the general public as possible. Powered by a 145-horsepower 1,176cc 3-cylinder engine (lifted from the Ultra 150) is fed by triple Keihin CDCV 40 carburetors and a single fuel pump, and features a water-jacketed exhaust system designed to separate cooling water from the expansion chamber, allowing exhaust gases to “flow dry and free from water vapor.”

This, all sitting in the belly of a hand-laid fiberglass hull (borrowing from the 1100 STX DI), the STX-R was stripped down and lightened for greater acceleration and aggressive “race-style” sponsons for more precise handling. All of this made the 2002 STX-R the fastest production-built watercraft on the market – rated conservatively at 63mph. The success of the STX-R has carried on to today – almost completely untouched – as the STX-15F, a testament to the craft’s hull design.

2002 Yamaha FX140

It had truly come down to the wire. Pressures from outside forces were squeezing the PWC industry to either clean up their act or shut down completely. Despite chirping from Honda that a 4-stroke watercraft was soon coming, Yamaha and Sea-Doo were in a neck-and-neck race to announce their 4-stroke runabout first. Both manufacturers learned of each other’s release date and scurried to unveil their 4-stroke watercraft on August 20th, 2001. Media were dumbfounded as to how to attend both events simultaneously.

In the end, beating out Sea-Doo’s GTX 4-Tec by merely a month, the 2002 Yamaha FX140 was first to the market, claiming itself as first. The FX140’s MR-1 was initially based off Yamaha’s successful four-stroke R-1 motorcycle engine, and cut emissions by 75-percent over carbureted two-stroke models of similar horsepower (140). The MR-1 entered the market as a fuel-injected, water-cooled 4-cylinder with double overhead cams, 20 valves (five per cylinder) and independent water-jacketed exhaust manifolds.

2004 Sea-Doo RXP 215

“It’s the first of the real muscle craft,” Greenhulk’s Jerry Gaddis admonished. Although the first supercharged 4-Tec 4-stroke belonged to the GTX SC, bumping the naturally-aspirated 155-horsepower up to 185 thanks to an increased 5-pounds of boost; Sea-Doo turned up the wick for the 2004 RXP. The increased boost pushed the all-new RXP above 200-ponies – a first for the industry – to 215. The two-seater configuration wasn’t fooling anyone, and an optional number plate cover was available shortly thereafter – squarely making it a one-seater.

With a 2.2-second 0-to-30mph acceleration time and a conservative 65.5mph top speed, the 2004 RXP was the catalyst that not only spurred the aftermarket to wholly accept digital fuel mapping, forced-induction and 4-stroke technologies otherwise ignored. This craft, covered in its Candy Apple livery, sparked the creation of the industry’s largest online forum (www.greenhulk.net) but modern PWC drag racing.

2007 Yamaha GP1300R

It was the end of an era. Marking 30 years since the first WaveRunner, the final 2-stroke Yamaha runabout was also one of its most terrifying. There were few watercraft more successful, more speed-hungry than the GP1300R. From 2003 to 2007, the GP1300R reigned as Yamaha’s nuclear option, raking in regional, national and world championships again and again. In fact, the legacy of the GP1300R continues today, not just in the modern GP now carrying its namesake, but also as a darling of aftermarket tuners.

To many, the hull resides atop the pantheon of the best designs from a factory. Slight changes marked the model years; 2003-04 made 165-horsepower and employed power valves. For 2005, power was increased to 170-horsepower and the power valves were dropped as well as welcoming a new jet pump. All were electronically fuel injected and came with bilge pumps. Although slightly heavier for its final year, the GP1300R still reached a GPS-reported top speed of 69-plus-mph.

2011 Kawasaki Ultra 300X

There was a time when the phrase, “It’s Kawi water” was significant. When introduced in 2007, the redesigned Ultra JetSki wielded an industry-leading 250-horsepower and rode atop a truly deep-V hull that broke and bashed its way through waves like a Coast Guard Cutter. A brief horsepower-war ensued between Kawasaki and Sea-Doo, requiring the Big K to up the ante significantly for 2011. Kawasaki worked closely with Eaton to create a true TVS twin-screw, roots-style blower pumping out 17 psi of boost. That’s 54-percent more than was pressed down the throat of the 260-horsepower 260X engine a year earlier.

To produce a true 300-horsepower, the 1,493cc plant also gained new hardened valves, a stronger cam chain, a revised exhaust camshaft and a new double-row oil cooler. Add to that a new 160mm jet pump (replacing the previous 155mm pump) and a new intake grate. Oh yeah, and let’s not forget the 300X being Kawasaki’s first JetSki to feature electric jet nozzle trim control and a fly-by-wire throttle body.

2014 Sea-Doo Spark

Perhaps to recent in our collective memory to truly be appreciated for what it is or the impact it has made on the PWC industry, the introduction of the Sea-Doo Spark in 2014 was a major watershed moment. Prior to the Spark, there was no such thing as the Rec-Lite segment. The Spark created that. Previously, the idea of a 90-horsepower, 400-pound 2-seater for $5,000 from the world’s largest manufacturer of PWC was unheard of.

Now, the Spark continues as one of the top 3-selling watercraft year-after-year, and almost exclusively responsible for ushering in a whole new demographic of first-time PWC buyers. Made from a lightweight proprietary PolyTec polymer composite and powered by a marinized Ski-Doo ACE 900 engine, the days of “two skis and a trailer for $10,000” were actually possible.

2017 Yamaha GP1800

We at The Watercraft Journal have heaped quite a bit of praise upon the Yamaha GP1800 and now, GP1800R (the latter of which earning back-to-back Watercraft of The Year awards). Of course, no quantity of accolades from us could match the vast number of podium finishes and world titles that this ski has racked up in its short two-and-a-half years. Add to that, absolutely stellar sales (particularly for a supercharged performance ski), and the GP seems unstoppable.

The hull and platform was designed as a fail safe if the economy were to tank (again like in 2009); meaning all other segments would be shut down and this one hull would have to “do it all” until things got better. Amazingly, through the use of Yamaha’s NanoXcel2 paired with its 1.8L SVHO engine, it pretty much can. We haven’t seen all that the GP1800 can do on the race circuit or on the showroom either, as the new “R” is sure to give the this platform another strong 5-to-6 years.